After the Lusitania sinking, the Wilson Administration had the telephone lines at the Germany Embassy tapped and ordered von Bernstorff and his staff to be placed under surveillance by the Secret Service. By January 1917, President Wilson had severed all relations with Germany, ordering von Bernstorff and his embassy staff repatriated to their homeland.

Following the war, von Bernstorff became a political mogul in Germany, serving in the Reichstag (German parliament) from 1921 to 1928. An activist for democracy, he later fell out of favor with the Nazi regime because of his outspoken support for the League of Nations and co-founding of an opposition party. In 1932, he went into self-exile in Switzerland, where he died, seven years later, of heart disease.

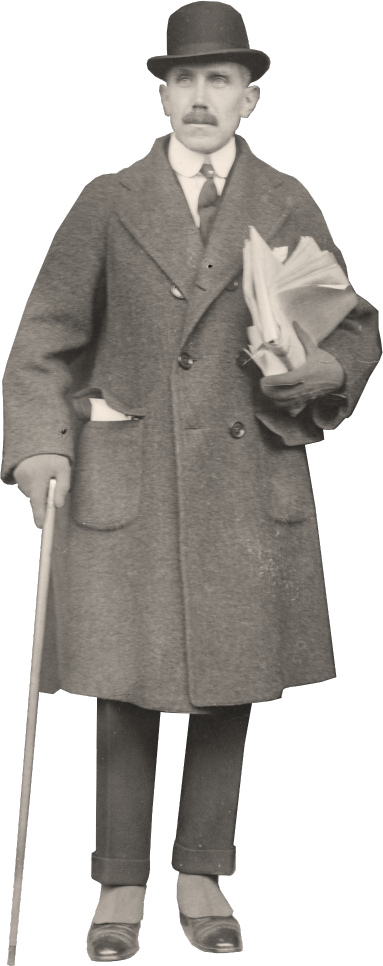

Captain Franz von Papen

Von Bernstorff was hardly the only emissary connected to espionage activities. German military intelligence also sought to make use of Captain Franz von Papen, the German Army Attaché in Washington, D.C. Born into a wealthy family, von Papen enlisted in the German Army as a young man and, after rising through the officer corps, was assigned as an attaché – an embassy position often used as a cover for overt spying activities.

At the direction of Ambassador von Bernstorff, von Papen established himself in New York City, the financial and commercial hub of America, where he continued to manage espionage and subversive operations without implicating the German Embassy. After receiving coded instructions directly from the Abteilung IIIb to disrupt shipments of military supplies and munitions to the Allied Powers, von Papen collaborated with two others: Captain Karl Boy-Ed, the German Navy Attaché at the Embassy, and U.S. citizen Paul Koenig, who was an intelligence operative and former security chief for a German shipping enterprise. It was Koenig who would directly supervise sabotage operations on the New York and New Jersey coasts. The men also made use of a purported bordello as a safe house. Located at 123 West 15th Street in Lower Manhattan, it was owned by a former German opera singer, and visited frequently by interned German sailors. Von Papen and other sabotage leaders used the site regularly to conduct meetings with operatives, store explosives, and plan their sabotage activities.

One of von Papen’s earliest enterprises involved forging American passports so German-Americans could return to the homeland and serve in the German Army. The falsified documents could also be used to facilitate the travel of German spies to Great Britain and France. Poorly managed, the scheme was shut down in early 1915. It was also counterproductive, as it led the State Department to start requiring photographs in passports and directly implicated both von Papen and Ambassador von Bernstorff in the false passport scheme.

Viewed unfavorably by many within the hierarchy of the German Foreign Service, von Papen largely squandered his opportunity in the United States to disprove his doubters. The attaché ultimately bungled several sabotage operations in North America, including a February 1915 attempt to destroy the Vanceboro International Bridge – an important shipping route between Canada and the United States – in eastern Maine. Despite his failures, however, von Papen was awarded the Iron Cross, Germany’s most prestigious military decoration.