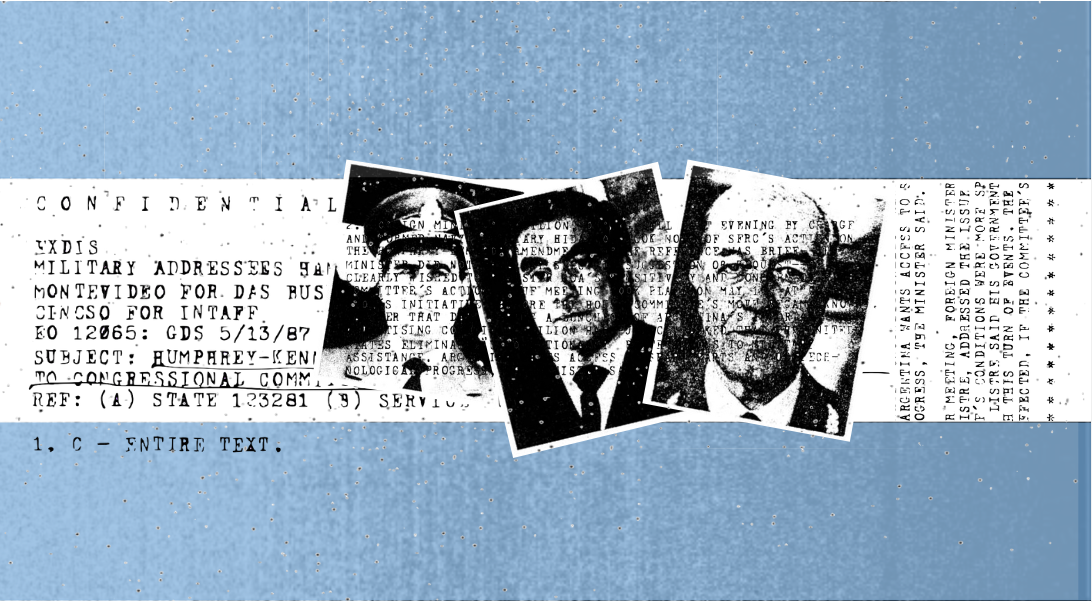

Argentina Declassification Project: History

Argentina's Military Dictatorship

Argentina: Before March 1976

For over a year prior to the March 1976 coup, U.S. government officials and other observers consistently characterized the situation in Argentina as “deteriorating.” Both the press and U.S. intelligence agencies reported on political instability and uncertainty, especially in coverage of the inner circle of President Isabel Peron, the Argentine congress, and military leaders.

Crime and terrorism disrupted daily life in Argentina, and due to Cold War foreign policy priorities, U.S. government agencies generally paid more attention to the threat of terrorism committed by ideologically leftist than by rightist groups. Leftist guerrilla groups operating in both the cities and the countryside—the Montoneros and ERP—seemed to be gaining followers and control over certain geographic areas, successfully financed their operations through kidnapping and extortion, sometimes targeted U.S. citizens, and increasingly seemed able to repulse the efforts of the Argentine security forces to contain them.

At the same time, right-wing death squads with links to the Peron government and the security forces, notably the Argentine Anti-Communist Alliance (Triple A), increasingly targeted labor leaders and left-wing Peronist political leaders as well as leftist guerrillas.

Ford Administration Policy, Through the March 1976 Coup

Throughout 1975 and into early 1976, U.S. officials in Argentina repeatedly warned Washington that a coup was likely due to crime, violence, and instability under the government of Isabel Peron. The coup came on March 24, 1976 when an Argentine military junta removed Peron from power. The U.S. gave limited support to the new government, through the end of the Gerald Ford Administration in January 1977.

On March 26, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger said in a staff meeting that he thought the new Argentine government “will need a little encouragement from us.” Kissinger met with Argentine Foreign Minister Cesar Guzzetti in June and October of 1976. At both meetings, Kissinger said that he wanted to see the Argentine government “succeed.”

U.S. officials in Buenos Aires and in Washington also reported on the ideology and actions of the junta, including about human rights violations, throughout 1976. Officials tried to glean the character of the new government, concluding that it would likely be “moderate” but that the U.S. government “should not become overly identified with the junta.” Officials also repeatedly wondered if junta president Jorge Videla, the commander of the army, had enough control over the security forces to end human rights abuses—or if an end to human rights abuses was even one of Videla’s goals.

In July, the U.S. Embassy in Buenos Aires reported to Washington that estimates of the number of people who had been illegally detained “run into the thousands and many have been tortured and murdered.” In response to the dramatically increasing volume of such cases, U.S. Ambassador to Argentina Robert C. Hill protested to the Argentine government concerning human rights abuses in May 1976. In July, Assistant Secretary of State Harry Shlaudeman told Kissinger that the Argentine “security forces are totally out of control” and that the U.S. would “have to wait until somebody surfaces to get a handle on this.”

In September, Hill protested again, directly to Videla, that “not one single person has been brought to justice or even disciplined” for violations of human rights. In response, Videla said that “Kissinger understood their problem and had said he hoped they could get terrorism under control as quickly as possible.”

Carter Administration policy

The Carter Administration’s emphasis on human rights in U.S. foreign policy heavily influenced its approach to Argentina. In addition, during 1977 and 1978 the Carter Administration’s policy toward Argentina was shaped by the Kennedy-Humphrey Amendment (P.L. 95-92, sec. 11), a Congressionally-mandated halt on all U.S. military aid, training, and arms sales to Argentina, which was enacted in August 1977 and went into effect on October 1, 1978.

The Carter Administration also had other goals for its policy toward Argentina. U.S. policymakers wanted to moderate and encourage an end to the military government and a return to elective democracy, prevent Argentine disputes with its neighbors from devolving into war, prevent Argentina from working towards becoming a nuclear power, and encourage the stabilization and growth of the Argentine economy, which suffered from high inflation rates.

Officials struggled to balance these competing interests, many of which required discussions with and persuasion of Argentine officials, with the new pressure from the White House, Congress, victims’ relatives, and NGOs to get the Argentine government to demonstrate real improvement on human rights issues. There were disagreements among U.S. officials about the rate at which the junta’s human rights record was improving, but no one at this stage tried to argue that the military government deserved the unwavering support of the United States.

By early 1977, most U.S. officials believed that the leftist guerrilla groups had been defeated, and that the vast majority of the continued detentions, torture, and disappearances were perpetrated by people or groups accountable to the Argentine government and unrelated to any real threat from the armed left. U.S. Ambassador Raul H. Castro continued to press the junta to improve its performance on human rights, to return to democracy, and, at times, to account for the missing and punish those responsible for abuses. The U.S. Embassy in Buenos Aires also continued to collect data on human rights abuses, documenting 9,000 kidnappings and disappearances and conducting interviews with those who had been detained or who were searching for missing relatives.

The disagreement inside the U.S. government was over exactly what tactics to use to change the regime’s behavior and how to identify the better actors within Argentina’s ruling circles. During 1977 and most of 1978, the impending new ban on arms sales, aid, and training provided the U.S. with some leverage, as did the U.S. vote on Argentine loans in International Financial Institutions (IFIs) like the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. However, policymakers did not always agree on how to use those points of leverage, or about what exactly to tell their interlocutors in the Argentine government about how the U.S. interest in promoting human rights would affect other areas of relations.

As early as May 1976 and throughout 1977, some U.S. policymakers thought Videla would act as the necessary “moderate.” When he spoke with U.S. envoys, Videla promised he could compel the junta to publish lists of the state’s prisoners, release a few high-profile prisoners, and release others into voluntary exile. Ultimately, these U.S. officials wanted to support Videla to help him balance the U.S. demand for improvements in human rights with the demands of Argentine military hardliners who opposed “concessions” to the U.S. on human rights.

These U.S. officials wanted the U.S. to vote in Argentina’s favor in the IFIs and argued for the approval of arms transfers before the Kennedy-Humphrey embargo went into effect, believing that these moves would support Videla’s claim to the junta presidency. Other U.S. policymakers did not trust Videla. They believed that maintaining pressure on Videla and the junta as a whole for improvements in human rights should be prioritized over other U.S. interests in Argentina. They wanted the government of Argentina to face concrete sanctions if it did not halt its abuses—they opposed arms transfers and wanted the U.S. to vote against Argentine loans in the IFIs.

Disappearances in Argentina slowed to a trickle by the early 1980s, but it is unclear whether this improvement was primarily due to pressure from the U.S., to an internal decision made by the Argentine junta in its war against perceived leftists, or to other factors. Carter’s human rights pressure also pushed the junta to look for allies elsewhere who were less focused on human rights, including in the Eastern bloc and the Soviet Union.

Argentina’s staunchly anticommunist junta signed two trade agreements with the Soviet Union in 1980, agreeing to provide 5 million tons of grain in 1980 and 22 million tons of corn, sorghum, and soybeans over the next 5 years—in defiance of Carter’s grain embargo on the USSR.

Reagan Administration Policy

The Reagan administration sought to improve U.S.-Argentine relations and focused on private diplomacy regarding human rights in Argentina. They worked to restore military ties between the two anti-communist counties and to weaken or overturn the 1978 Kennedy-Humphrey Amendment’s restrictions on military aid to Argentina.

Reagan and his Secretary of State, Al Haig, viewed Carter’s public criticisms of Argentina as misguided and thought that any valid concerns about human rights abuses by the Argentine military should be raised privately. Thus, when the Argentine military junta replaced Videla with Roberto Viola as president in March 1981, Haig told Viola that there would be “no finger-pointing” regarding human rights, adding: “if there are problems, they will be discussed quietly and confidentially.” Reagan agreed, telling Viola that “there would be no public scoldings and lectures.”

With warmer bilateral relations secured and disappearances apparently on the wane, the Reagan administration felt that it could make progress on many of the central issues faced by Carter: stabilization of an economy that was in deep recession and carrying massive foreign debt, nuclear proliferation and the ratification of the Treaty of Tlatelolco, Argentina’s lack of participation in the grain embargo against the Soviets, and a return to electoral democracy. Reagan was also interested in securing Argentine assistance in securing his administration’s goals in Central America, particularly in El Salvador.

Optimism waned when Leopoldo Galtieri, installed as president by the junta in December 1981, decided that invading the Falkland (Malvinas) Islands would shore up his government, which faced dire economic problems, labor unrest, and growing public displeasure with military rule. When Argentina lost the war against the United Kingdom over the islands, the junta was widely discredited for its human rights abuses, economic mismanagement, and the loss of the war.

Non-governmental groups like Amnesty International and U.S. Senators including Alan Cranston and Edward Kennedy called for justice regarding the thousands of “disappeared” in Argentina. In December 1982, Assistant Secretary of State Elliott Abrams privately told Argentine Ambassador to the U.S. Lucio Alberto Garcia del Solar that the question of “children born to prisoners or children taken from their families” was “the gravest humanitarian problem” that the military government of Argentina faced, as it tried to negotiate an amnesty with political parties looking toward elections that would restore democracy in Argentina.

The democratic election in October 1983 brought about the civilian leadership of Raúl Alfonsín, but the country’s economic problems, which had been exacerbated by the war in the South Atlantic, remained. Alfonsín struggled to chart a new role for the military in Argentine society and to find a politically workable balance between prosecutions and amnesty for the perpetrators of human rights abuses. He also needed U.S. assistance with solving the country’s foreign debt crisis.

Explore the Argentina Declassification Project:

OVERVIEW & ORIGINS

SCOPE OF RESEARCH

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

RESPONSIVE RECORDS

RETURN TO HOME